From rather obscure and humble beginnings in Australia in the late 1970’s, permaculture has grown in just three decades into a vibrant worldwide movement.

Permaculture founders Bill Mollison and David Holmgren observed the devastating effects that agriculture and human settlements were having on the ecology of their homeland and they asked the simple question, “How can we meet human needs by patterning human developments after natural systems, rather than destroying natural systems?” This basic quest continues to the growth and proliferation of permaculture practitioners and communities around the globe today.

Permaculture is at heart an integrative and eclectic movement. It draws deeply from traditional knowledge and from contemporary scientific understanding in an attempt to weave human culture back into the fabric of living ecosystems. Permaculture is also very contextual. If they are to succeed, permaculture designs must be deeply rooted in the particular place in which they occur: geography, ecology, climate, culture, economy, and the needs and priorities of the resident human community.

While it is very difficult to concisely define a movement as broad and as diverse as permaculture, there are several commonly used descriptions offered up by several key voices in the permaculture movement:

“The conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystemswhich have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems.”

“Consciously designed ecosystems, which mimic patterns and relationships found in nature,while yielding an abundance of food, fiber, and energy for provision of local needs.”

“Permaculture is the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystemswhich have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems. It is the harmonious integrationof landscape and people providing their food, energy, shelter, and other material and non-material needsin a sustainable way.”

“A set of techniques and principles for designing sustainable human settlements.”

“The Regeneration of people and place.”

Scope of the Work

The term “permaculture” was first coined by Mollison and Holmgren as a contraction of the words: permanent + agriculture. This linguistic innovation reflected the initial concern for creating an alternative agricultural system that would be sustainable over the long term and that would be comprised largely of perennial species, much like a forest system.

As their thinking evolved, however, Mollison and Holmgren argued for another, somewhat more radical formula; permaculture = permanent + culture. This development reflected the insight that much more than agricultural methods need to change if we are to truly alter the destructive path that we are on. True sustainability requires the transformation of the basic human patterns that have brought us to the crisis point we are at today. Thus permaculture calls for a cultural shift that includes not only how we feed ourselves (agriculture), but also our housing, transportation, economy, social organization, education, energy, health, and the very way in which we understand our relationship to the world around us (i.e. spirituality).

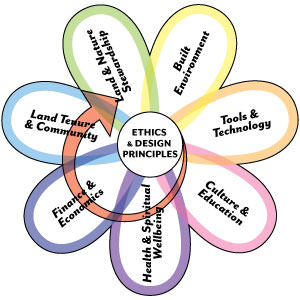

This broad, integrative and transformative vision of permaculture may be best represented by the permaculture flower conceived of by David Holmgren. At the core of permaculture is a set of ethics and design principles that can be applied to a wide range of domains. Permaculture begins small and radiates outward to embrace the needs of the wider community and ecology. There are many different expressions of permaculture, from gardens to community organizations to energy systems to water systems, etc. Permaculture cannot be reduced to any one expression yet it is the system that bring all of these components together.

The scope of permaculture can range from small systems on balconies, in households or urban yards, to acreages, farms, ecovillages, communities, municpalities and beyond. There is no single template for a permaculture system or design and there is no one way that a permaculture system looks. What drives the design is the careful observation of the particular place in which it is located and the specific outcomes or yields desired from the system. For most permaculture practitioners, beauty is an important consideration and is one yield that is designed into the system. The aesthetics of a given design are as diverse and as unique as the creativity of the designer.

Ethics

From the very early conception of the permaculture vision, Mollison and Holmgren proposed three foundational ethical principles for the movement:

* Care of the Earth ~ Care of People ~ Sharing the Surplus *

Earth Care suggests that natural systems and biodiversity be the primary reference point for all human activity. Additional damage to the planet’s living and non-living systems needs to be halted and we must actively work towards regeneration and healing where harm has been done. Permaculture designs can restore soil, create habitat for diverse species, replenish water reserves and create the conditions in which life can flourish.

As a living species on this planet, humans also have needs and these needs must be taken into account in any permculture design. The People Care ethic would challenge the familiar dichotomy between us and nature, suggesting instead that we need to weave human needs into the functioning and health of the wider ecosystem. Permaculture designs will typically provide for a variety of human needs such as food, water, energy, medicine, building materials, beauty, community and more.

Rather than a paradigm of hoarding, Sharing the Surplus suggests that we cannot deny other people and other species their needs through our own over-consumption. Indeed, we will live a fuller and more meaningful life when others too can thrive. This is an ethic of social and ecological justice and a call to live in right relationship and with balance. Good designs will in time create a surplus (be it of biomass, food, water, wisdom, income, etc.) that can be shared with others.

As diverse as the many expressions of permaculture are, these three ethical principles are common to permaculture initiatives throughout the world. If one were to question whether a given landscape design, garden, community or other project is really permaculture, these three ethical principles can function as the touchstone to make this assessment. Are the three ethical principles upheld in a given design? If they are, then we can comfortably call it permaculture.

Design Principles

While permaculture has an ethical foundation and a broad and integral vision of sustainability, it does not stop there. Permaculture is a highly practical and concrete philosophy that offers a toolbox of design principles and strategies for creating systems that are regenerative and resilient. These design principles and strategies are most fully articulated in Bill Mollison’s Permaculture – A Designer’s Manual. The design principles provide the how to of the design process and are considered to be guiding tools rather than dogmatic templates.

The design principles and strategies can be applicable to a wide range of domains as demonstrated by the permaculture flower above. For the purpose of this discussion, however, we will consider them primarily for the development of landscapes and outdoor living systems.

Some of the key permaculture design principles and strategies include:

Protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labour.

Developing a thorough understanding of the design site including its history, topography, functioning ecology, soil conditions, sunlight patterns, movement of water, human engagement in the space, wildlife patterns, etc. is a critical step in preparing to make any changes. Sometimes this is referred to as “sector analysis.” If the site is not properly understood, a variety of errors in the design can occur.

Start small. Make the least change for the greatest effect.

The best permaculture designs begin small and are scaled-up after positive affirmation or feedback from the design system itself is received. In practical terms, we need to learn our lessons and make our mistakes on a small scale rather than a large one. This saves time, effort and money. Sometimes a simple intervention or change or will provide greater results than a larger, more expensive one.

Obtain a yield.

The yields of a system are theoretically unlimited.In technical terms, a yield is any product of the created system that can meet a human or non-human need. Some yields will need to be invested back into the system (i.e. biomass into soil) while others can be enjoyed by the people who are engaged with it. Examples of potential material yields from a system include food, water, energy, medicine, fibre, building materials, biodiversity, soil, bio-mass, etc. while non-material yields may include beauty, learning, wisdom, solitude, recreation, community, income, etc. The nature of nature is that it becomes increasingly productive over time (i.e. cleared land eventually yields a forest), and the yields of a well-designed system will eventually generate a surplus.

Stacking Functions #1

All elements in the design should serve multiple functions. All things in nature do more than one thing, they are embedded in a myriad of relationships performing a variety of services for the life community in which they reside. So too does each element in a permaculture design play multiple roles and offer multiple yields. A well-chosen and placed tree can provide food, shade, cooling, biomass, beauty, building materials, a structure for other plants to climb, habitat for many species, recreation and many other functions. A fence can be made of plants that provide privacy, food, habitat, beauty, and biomass. A water cistern can also store heat for a greenhouse or function as a structure as part of a building.

Stacking Functions #2

All functions in the system should be served by multiple elements. This principle is essentially one of planning redundancy into the system so there is less fragility and more resilience. We may have a variety of strategies to meet the water needs of the system including household grey water use, rooftop catchment, high soil organic matter, landscape contours such as swales or ponds, in addition to the conventional water sources available to us. In order to support the key element of food production we may employ a variety of food growing models including annual vegetable beds, edible perennials, edible forest gardens, mushroom cultivation and small livestock such as bees, rabbits or chickens. In short, don’t put all your eggs in one basket!

Stacking Functions #3

Stack elements in vertical and horizontal space as well as in time. Particularly in smaller urban lots, we want to be able to grow as much as possible in a vertical plane to maximize the amount of bio-mass we can generate and the food and other yields we can create within the system. This might include multi-layered growing areas, espalier fruit trees, wall-mounted systems, and green roofs. Similarly, we will design the space along temporal lines, ensuring that the annual vegetables are planted in succession or that perennial systems are evolving towards a state of succession in which they are at maximum productivity, and that there are younger plants prepared to replace older ones. Edible Forest Gardens are a good example of permaculture systems that are stacked in both space and time.

Maximize diversity. Diverse elements with diverse functional relationships create resiliency.

Most natural systems are highly diverse and they derive their resilience through the multiplicity of synergistic relationships occurring among diverse species. We can observe this same dynamic in human communities. Where there are people of diverse points of view, skills, resources and interests, and when these people are able to form effective partnerships with each other, we create resilient and highly functional communities. Designing diverse elements and relationships into a landscape takes a great deal of knowledge, patience and effort and it is not an exact science. Some of this is experimental and we will never achieve the level of elegance and efficiency embodied in nature’s own designs, though this is the goal we are striving towards.

Catch and store energy. Cycle resources through the system.

Energy is constantly flowing through our universe, flowing through all matter and through all living things including ourselves. A permaculture design seeks to catch as much energy as possible (through plants, thermal mass, and perhaps simple technologies such as cold frames, solar greenhouses, and more complex technologies such as photovoltaic panels) and to recirculate it through the system as many times as possible before it finally flows outward. We can think of the energy of the sun becoming embodied in a tree. The leaves of the tree can feed a cow or a goat, the manure can be processed through a biogas digester, the slurry from the digester can be used in creating worm compost, the excess worms can feed fish, the worm compost can be used to grow plants, etc. With each transaction, some of the original energy captured in the leaves of the tree is cycled yet again. Energy animates the system and over time, as the system matures, it will be capable of catching and cycling more and more energy.

Use local, on-site resources and biological resources.

From re-purposing and reusing materials like broken concrete, tires or bricks to growing our own fertilizers (special plants that build soil fertility such as legumes and other “dynamic accumulators”), to using living systems such as “rock and reed beds” to treat household grey water, our goal is to bring in as few outside resources into the system as possible. Most systems will require some outside inputs in the initial phases but this should decrease over time. In urban areas, there is an overabundance of “waste materials” that we can capture and use in our system.

Produce no waste. Pollution is an unused resource.

Waste is a uniquely human phenomenon. In natural systems, the output of one organism becomes food for another organism. A permaculture design seeks to connect yields from one element in the system to the needs of other elements in the system. Minimally, all of the organic material generated on site can be easily absorbed back into the system to feed the soil and ultimately the plants, animals and ourselves. Some permaculture designs will consider safe and appropriate ways to utilize human wastes (urine, feces, hair, etc) rather than using a limited and valuable resource such as potable water to flush them “away”.

Relative location. Create functional relationships between diverse elements in the design. Integrate, don’t segregate.

This is the heart of the permaculture design process. Rather than a bunch of disparate elements that have no functional relationship with each other, we want to chose and locate all elements so that they are performing meaningful services to each other. In this regard we must consider all of the key elements of water, soil, energy, plants, animals, fungi, appropriate technologies and people in the equation. For example we have a randomly placed a greenhouse, a chicken coop, a tree, a garden, and a pond on our property in which case they provide few services for eachother. However we can situate these elements so they compliment one another: the tree can cool the house, shade the greenhouse, provide forage for the chickens and biomass for the garden; the greenhouse can help heat the house, clean household grey water and deliver it to the pond; the chickens can weed the garden and keep down the slugs in a moveable pen (“chicken tractor”); the pond can be a source of nutrient and irrigation for the garden and beauty for the people in the house, etc.

Law of Return: Whatever we take, we must return. Do not export more biomass (carbon) than can be fixed within the solar budget.

In order to ensure that a system can thrive, we must be sure the needs internal to the system itself are being met. If we harvest out all of the bio-mass all of the time, the soil will loose its complex microbial life and eventually its fertility. Natural systems build up carbon over time where as human systems remove carbon from the soil and from biomass resulting in excess carbon in the atmosphere.

Maximize edge.

“Edge”, in ecological terms, is the dynamic place where two different ecosystems meet, i.e. a meadow and a forest, mountains and ocean, prairies and foothills. These edges tend to have the most ecological diversity and the most productivity. It is no surprise that most early human settlements occurred along edges as the availability of resources if very high in these zones. Our designs can mimic these ecological edges with both increased productivity, bio-diversity and aesthetic interest. Furthermore, permaculture designs can create social edges – places where dynamic human interactions can occur. This may be a front yard edible forest garden that attracts the questions, and arouses the curiosity of neighbours and opens the door to collaborative possibilities.

“The problem is the solution.”

Very often we encounter a “problem” in our landscape or our community as an entirely negative phenomena. Permaculture would have us re-frame this conception, suggesting that within the heart of the problem itself, if well understood, lies an opportunity or even a little bit of gold. An old tree stump that continues to sucker up can be considered a biomass factory for the compost pile; that area that is always wet or tends to flood might be begging for a pond; our cranky old neighbour might be sitting on a wealth of experience, wisdom, or energy that we just haven’t yet figured out how to tap into.

Plan for decreasing intervention over time

– “the designer becomes the recliner”.

Bill Mollison was fond of saying that “work can be considered a failure of design.” While all systems do require some work, good designs will require less as they are following nature’s rules rather than our own impositions. Any landscape will constantly try to revert back to what its natural state was. By designing a system that mimics that natural state while also providing yields that we need, we are taking much of the work out of the equation. Indeed, our greatest role in the system may become harvesting those yields and admiring the beauty and the biodiversity that is around us.

Permaculture Education

The standard unit of permaculture education is the 72 hour Permaculture Design Certificate program, or PDC. This training covers the standard international permaculture curriculum as set fort in Australia but it also varies depending on the context, the culture and the teacher. In addition to the PDC, there are many 1-3 day introductory permaculture workshops available, and, in some cases longer term permaculture internships, teacher trainings and diploma programs.

From the earliest beginnings, Mollison and Holmgren intended the vision of permaculture to be shared throughout the world. They encouraged students to become teachers once they had completed their own PDC, undertaken some permaculture design and installation work, and assisted other more experienced teachers in their courses.

Permaculture is a fundamentally democratic movement. There is no master plan or no firm control over who teaches permaculture or who calls themself a permaculture teacher. This is a growing community that is finding many unique expressions around the world as individuals and communities seek to take control of their own lives and to foster positive change. There are regional, national and international permaculture convergences or gatherings, where people gather to support and learn from eachother.

Permaculture in Canada

While permaculture began in Australia in the mid 1970’s and rapidly spread throughout the southern hemisphere by the late 1970’s, the movement is relatively new to Canada. This may in part be due to the fact that permaculture grew out of the tropical and subtropical regions and it has taken some time for this vision to be understood and articulated for the temperate and northern regional context. Approximately 15 years ago, the first permaculture courses were offered in Canada in the southern interior of BC and on the west coast, having migrated up from California and the Pacific northwest of the United States. This was soon followed by permaculture courses and communities emerging in Quebec and Ontario. In the last 5-7 years, however, permaculture has seen tremendous growth in Canada with some level of permaculture activity in most Canadian provinces. Many Canadians have received permaculture training overseas and, upon return to their home communities have attempted to organize permaculture communities and activities.

Canadian Expressions of Permaculture Today

Permaculture Workshops

As in most countries, the main vehicle for transmission of permaculture vision and practice is through the standardized 2-week Permaculture Design Course (PDC) and through one or two day Introduction to Permaculture workshops. These are now happening with considerable regularity in BC, Alberta, Quebec and Ontario, with less frequent occurrence in other provinces. Typically, these courses are led by graduates of other PDC’s, often in partnership with more experienced permaculture teachers from other regions. According to the philosophy of permaculture, graduates of PDC’s are encouraged to find mentorship from more experienced teachers to move into a teaching role.

Permaculture Institutes

In addition to permaculture training opportunities, a number of permaculture practioners in Canada have formed organizations or institutes to facilitate their work. These are typically small, private organizations that offer courses, permaculture design services, consulting, research and, in some cases, permaculture design installations. (See list below).

Permaculture Guilds

In many cities or regions in Canada, people interested in permaculture have formed “guilds” or networking groups to support on-going permaculture activities and learning. The Edmonton Permaculture Network, for example, has close to 2000 members/subscribers. Members of the network organize regular learning potlucks, work bees, displays at community events and a list serve that encourages sharing of resources, ideas, and permaculture initiatives. Vancouver has a very well-established permaculture network and list serve that has been operating for many years. A number of years ago, there was a loose national affiliation of permaculture groups in Canada and a publication called “The Swale”, although this entity is currently inactive.

Rural Projects

A growing number of farmers and other rural landholders in Canada are exploring permaculture principles as a pathway to creating sustainable, productive, diverse and ecologically resilient agricultural systems. Many of these are also certified organic farms and are connected through their provincial and national affiliations. The Canadian Organic Grower (COG) features regular articles on permaculture in their national magazine. Some of these permaculture farms host Woofers or sponsor Permaculture Design Courses as part of their mission and value-added income generation activities.

Urban Projects

Perhaps the fastest growing permaculture sector in Canada is within the urban environment. There has been a flourishing of home-scale permaculture development as urban residents attempt to apply permaculture principles to their homes and yards. Some of these examples include intensive annual and perennial food production, edible forest gardens, grey water and rain water harvesting systems, natural building and alternative energy systems, integrated greenhouse systems, biodiversity enhancement, mushroom production and the integration of small livestock such as chickens or bees (legally or otherwise).

Beyond the home-scale, there is a range of community projects inspired by permaculture principles showing up in Canadian cities. These initiatives include: rooftop gardens, community gardens (particularly those that include perennial systems as well as vegetable gardening), fruit sharing programs, backyard sharing programs, edible landscaping on public lands, rewilding/biodiversity initiatives, guerrilla gardening, school projects, urban food production social enterprises, and many resource sharing and community building activities.

Ecovillages

The Global Ecovillage Network movement grew out of the same roots as the permaculture movement and the two remain affiliated cousins. In the past decade, numerous ecovillage projects have emerged in Canada and many more are in planning processes. What differentiates ecovillage projects from other intentional communities or cooperative housing, is the particular focus on and commit to an ecological way of living and organizing community life. Most of these projects have a sufficient land base to allow for a measure of food self-sufficiency and on-site economic activities. Some ecovillages, such as OUR Ecovillage on Vancouver Island, become hubs for permaculture learning with regular PDC’s and affiliated training opportunities in natural building, community design, non-violent communication, conflict resolution, and other themes.

Some Permaculture Organizations

and Resources in Canada

Big Sky Permaculture (Calgary, AB)

Eco-village Network of Canada (National)

Edmonton Permaculture (Edmonton, AB)

Environmental Design Collaborative (Ontario)

Gorgeous and Edible Landscaping (Olds, AB)

Jasper Place Permaculture (Edmonton, AB)

Kootenay Permaculture Institute (Winlaw, BC)

Montreal Permaculture Guild (Montreal, QC)

OUR Eco-village (Vancouver Island, BC)

P3 Permaculture Design (Montreal, QC)

Pacific Permaculture (Denman Island, BC)

Passionate Permaculture (Lund, BC)

Permaculture Design Magazine (North America, formerly Permaculture Activist)

Permaculture BC (BC)

Permaculture Insitute of Eastern Ontario (Ottawa, ON)

Permaculture Ottawa (Ottawa, ON)

Permaculture Powell River (Powell River, BC)

The Permaculture Project of GTA (Toronto, ON)

Seven Ravens Permaculture Academy and Eco Forest (Saltspring Island, BC)

Sustainable Living Network (Ontario & beyond)

The Urban Farmer, (Powell River, BC)

Verge Permaculture (Calgary, AB)